Signed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt on March 9, 1933, the legislation was aimed at restoring public confidence in the nation’s financial system after a weeklong bank holiday.

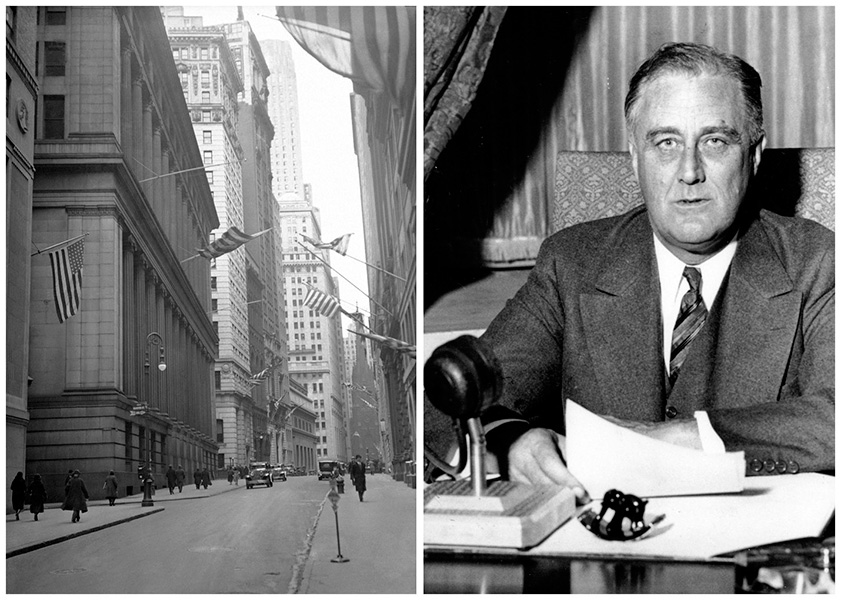

President Franklin Roosevelt signing the Emergency Banking Act (Photo: Bettmann/Bettmann/Getty Images)

by Stephen Greene, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis“The emergency banking legislation passed by the Congress today is a most constructive step toward the solution of the financial and banking difficulties which have confronted the country. The extraordinary rapidity with which this legislation was enacted by the Congress heartens and encourages the country.”

—Secretary of the Treasury William Woodin, March 9, 1933

“I can assure you that it is safer to keep your money in a reopened bank than under the mattress.”

—President Franklin Roosevelt in his first Fireside Chat, March 12, 1933

Immediately after his inauguration in March 1933, President Franklin Roosevelt set out to rebuild confidence in the nation’s banking system. At the time, the Great Depression was crippling the US economy. Many people were withdrawing their money from banks and keeping it at home. In response, the new president called a special session of Congress the day after the inauguration and declared a four-day banking holiday that shut down the banking system, including the Federal Reserve. This action was followed a few days later by the passage of the Emergency Banking Act, which was intended to restore Americans’ confidence in banks when they reopened.

The legislation, which provided for the reopening of the banks as soon as examiners found them to be financially secure, was prepared by Treasury staff during Herbert Hoover’s administration and was introduced on March 9, 1933. It passed later that evening amid a chaotic scene on the floor of Congress. In fact, many in Congress did not even have an opportunity to read the legislation before a vote was called for.

In his first Fireside Chat on March 12, 1933, Roosevelt explained the Emergency Banking Act as legislation that was “promptly and patriotically passed by the Congress . [that] gave authority to develop a program of rehabilitation of our banking facilities. . The new law allows the twelve Federal Reserve Banks to issue additional currency on good assets and thus the banks that reopen will be able to meet every legitimate call. The new currency is being sent out by the Bureau of Engraving and Printing to every part of the country.”

The Act, which also broadened the powers of the president during a banking crisis, was divided into five sections:

In that Fireside Chat, Roosevelt announced that the next day, March 13, banks in the twelve Federal Reserve Bank cities would reopen. Then, on March 14, banks in cities with recognized clearing houses (about 250 cities) would reopen. On March 15, banks throughout the country that government examiners ensured were sound would reopen and resume business.

Roosevelt added one more boost of confidence: “Remember that no sound bank is a dollar worse off than it was when it closed its doors last week. Neither is any bank which may turn out not to be in a position for immediate opening.”

What would happen if bank customers again made a run on their deposits once the banks reopened? Policymakers knew it was critical for the Federal Reserve to back the reopened banks if runs were to occur. To ensure the Fed’s cooperation to lend freely to cash-strapped banks, Roosevelt promised to protect Reserve Banks against losses. In a telegram dated March 11, 1933, from Treasury Secretary William Woodin to New York Fed Governor George Harrison, Roosevelt said,

“It is inevitable that some losses may be made by the Federal Reserve banks in loans to their member banks. The country appreciates, however, that the 12 regional Federal Reserve Banks are operating entirely under Federal Law and the recent Emergency Bank Act greatly enlarges their powers to adapt their facilities to a national emergency. Therefore, there is definitely an obligation on the federal government to reimburse the 12 regional Federal Reserve Banks for losses which they may make on loans made under these emergency powers. I do not hesitate to assure you that I shall ask the Congress to indemnify any of the 12 Federal Reserve banks for such losses.”

Was the Emergency Banking Act a success? For the most part, it was. When banks reopened on March 13, it was common to see long lines of customers returning their stashed cash to their bank accounts. Currency held by the public had increased by $1.78 billion in the four weeks ending March 8. By the end of March, though, the public had redeposited about two-thirds of this cash.

Wall Street registered its approval, as well. On March 15, the first day of stock trading after the extended closure of Wall Street, the New York Stock Exchange recorded the largest one-day percentage price increase ever, with the Dow Jones Industrial Average gaining 8.26 points to close at 62.10; a gain of 15.34 percent.

Other legislation also helped make the financial landscape more solid, such as the Banking Act of 1932 and the Reconstruction Finance Corporation Act of 1932. The Emergency Banking Act of 1933 itself is regarded by many as helping to set the nation’s banking system right during the Great Depression.

The Emergency Banking Act also had a historic impact on the Federal Reserve. Title I greatly increased the president’s power to conduct monetary policy independent of the Federal Reserve System. Combined, Titles I and IV took the United States and Federal Reserve Notes off the gold standard, which created a new framework for monetary policy. 1

Title III authorized the Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC) to provide capital to financial institutions. The capital injections by the RFC were similar to those under the TARP program in 2008, but they were not a model of the actions taken by the Fed in 2008-09. In neither episode did the Fed inject capital into banks; it only made loans.

Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. “Documents and Statements Pertaining to the Banking Emergency, Presidential Proclamations, Federal Legislation, Executive Orders, Regulations, and Other Documents and Official Statements, Part 1, February 25 - March 31, 1833.” 1933, https://fraser.stlouisfed.org/title/709/item/23564.

History Matters, the U.S. Survey Course on the Web. “‘More Important Than Gold’: FDR’s First Fireside Chat.” Accessed September 30, 2013, http://historymatters.gmu.edu/d/5199/.

Silber, William L. “Why Did FDR's Bank Holiday Succeed?” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Economic Policy Review, July 2009, 19-30.

Written as of November 22, 2013. See disclaimer.